The first case I wrote an expert opinion on was the use of a chokehold during an arrest. It had been applied while the suspect (our client) was handcuffed. The result – he ended up a quadriplegic and died one year after the case was settled.

Over the years I have seen numerous examples of their misapplication, yet the debate over safety and value still remains. One peer reviewed research study on vascular neck restraints deemed it “a safe and effective force intervention”; however, it also cautioned that “outcomes could vary in different populations”. Although interesting from an academic viewpoint, the conclusion has serious shortcomings outside of the laboratory setting.

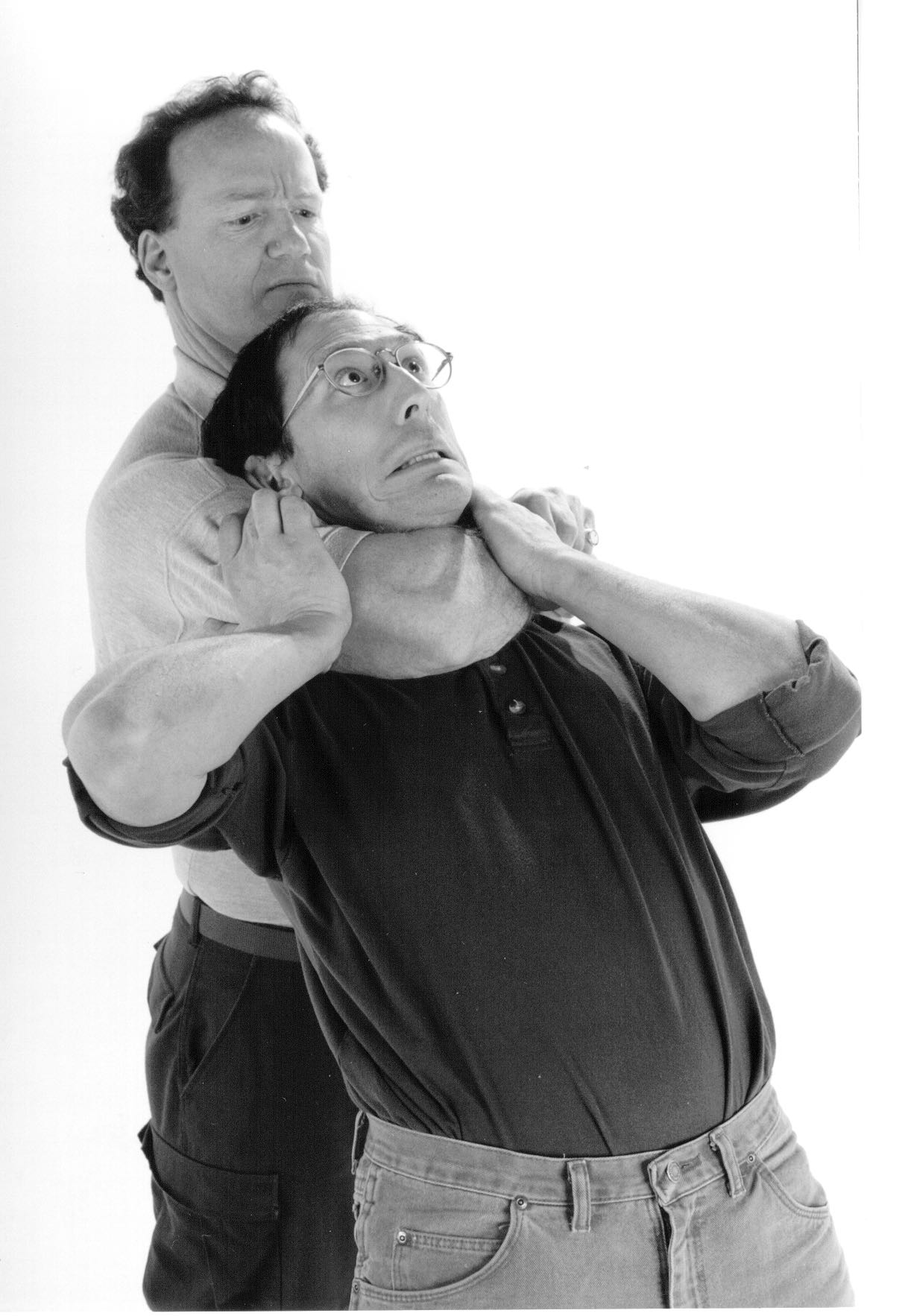

So, what are the problems with neck restraints and chokeholds? To better answer this question we should first examine where these types of techniques come from. One source is combat judo or jiu-jitsu and wrestling. Here, the holds are applied in controlled situations (sport) or in combat situations where residual damage is not a consideration. In eastern martial arts all of the techniques that apply direct pressure to the neck are labelled ‘strangulation’ methods. This means that serious injury or death are recognized as viable outcomes. (When I trained with the Chinese Special Forces, a variation of the chokehold was taught as a sentry removal technique.)

The question then becomes “what happens when neck restraints and chokeholds are introduced into law enforcement or security training?” Typically, the instruction and practice suffers from two root deficiencies: inadequate and improper training.

The most obvious shortcoming is that officers do not undergo either extensive training in the technique nor do they practice it regularly. As a result, they fail to obtain a high degree of proficiency in its use.

Another shortcoming is that the techniques are presented under ‘ideal’ conditions – typically a well-lit gymnasium, on mats, and under instructor supervision. On the ‘street’, none of these conditions are present. The terrain is wet, uneven, gravelled or littered; lighting levels may be poor. The suspect is non-compliant (opposite of your training partner in class). Here, the technique may have been initially applied correctly; however the suspect’s movement causes the officer to apply pressure incorrectly or at the wrong place. Because the officer is operating under stress, excessive pressure may be applied to the neck region to (re)gain compliance. Damage to the hyoid bone, dislocation of cartilage, stroke, heart attack and spinal injuries are just a few of the negative outcomes related to its misapplication.

In the case of the research study other variables were also in play. All participants were volunteers; physically fit; no relevant prior medical history; and free of medications. These variables are most often not the case in ‘real life’ as suspects tend to be intoxicated, on drugs (or off their medication) or in other altered mental states (AMS). While the experimental data my be valid, the general statement “a safe and effective force intervention” is not.